For some reason I brought a copy of the new Grant Morrison / Chris Burnham book Nameless. And a little while after I went to go see that new High-Rise film. I had some thoughts about both plus meaning and stuff and how it works and things like that and so figured that maybe it would be a good idea to write some of it down. So here you go (thanks to Mazin for his comments which I have included within…).

Right. Let’s do this.

For me – Grant Morrison comics are like magic eye pictures.

And yes I probably mean that in a bad way (sorry).

For those of you that don’t know: magic eye pictures are these stupid things that don’t work. It’s like a screwy picture and you’re supposed to focus your brain and unfocus your eyes and count backwards from 10 and then breathe out at the same time and this 3D image will spring up in front of you. Or something. I dunno. They always seemed to me like some sort of conspiracy, with me on one side bursting several blood vessels to try and get it to work and everyone else on the other side tittering behind their hands.

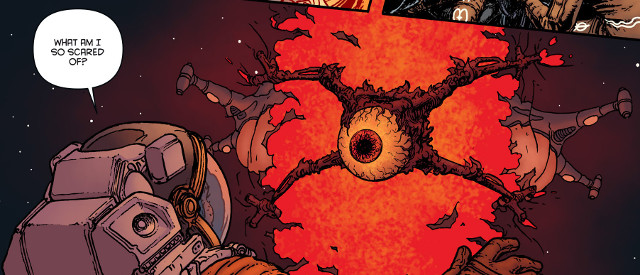

His new book Nameless (just out in collected form! Art by Chris Burnham! Colours by Nathan Fairbairn! Rated M for Mature!) is Morrison turned all the way up to 11. I mean: at some point one character remarks: “It’s like the goddamn Exorcist meets Apollo 13” which (urg!) really Grant? Could you please stop trying to pitch your comic in the middle of me reading it? I mean: I know Mark Millar is getting all his books made into movies: but come on dude. Also: technically it’s way more Inception meets Event Horizon: so you know – get it right.

Going from the comic people I know and seeing things posted up on blogs here and there Nameless has mostly been given many thumbs up. Proper good Morrison horror comic or whatever. But yeah – sadly for me – again it feels like everyone else drank the Kool Aid and all I’ve got is Vimto.

One of the sentences I hate most is “well – I guess it’s all subjective isn’t it?” which (in my experience anyway) is always kinda used as a way to shut down the conversation you know? Kinda like: well hey: here be monsters so let’s stop talking and return to the world of objective certainty. I mean: ok if you’re 16 then it’s ok: because back then it’s quite the revelation but past that I mean – have you just not been playing attention? I mean it’s like saying: “well – I guess everything is just made of words isn’t it?” because hey the answer is: yes it is. So let’s go explore further and see what he can come up with. Because your subjective isn’t the same as my subjective: expect tho – maybe there are bits that are the same? Maybe there are bits that are different? And – oh my – what are the reasons for these? How did we reach the subjective points we’ve got to? And is it possible maybe that by talking about our subjectivities we can change them?

Doing the online dating thing: there’s this one where you have to answer questions to give you percentage points to match with other people. One of my absolute favourites is: “Do you think everything happens for a reason?” I mean: I’m scared to answer it because it seems like it’s one for people who are big into their religion and everything: but oh my god yes – I do think everything happens for a reason: especially when it comes to humans and the stuff that we think. You know ideology ideology ideology and all the rest of it. Speaking personally – growing up I thought that the stuff I thought was stuff I had decided myself: and only getting older did I start to realise how that’s not true. That ideas exist in the world before we are even born and shape how we see the world and how the world sees us and etc

A good example maybe (or an example anyway): there’s this children’s book that I like to read at the Storytimes I do at work called Dear Zoo. Starts off with: “I wrote to the zoo and asked them to send me a pet. They sent me…” Cut to various types of animals. An Elephant. Only he’s too big. So I sent him back. A lion. He’s too fierce. So I sent him back. A camel. He’s too grumpy. So I sent him back. A snake. He’s too scary. So I sent him back. And so on. Last week I’m about to start running this book out (I know from the description it sounds kinda lame: but it’s got bits that fold out plus you can get them to make the noises of the animals: so it’s actually pretty cool: so yeah shut up) when I get the good idea of gender-swapping the animals. Because you know: we live in a sexist patriarchy and I should try and do my part to be a good feminist and help programme these children’s minds so that they don’t think that “He” is the default, right? Only – ha! – what I didn’t realise is that (omg) thanks to a lifetime of living in a sexist society if you genderswap the animals – what seems like a nice innocent kinda neutral children’s book suddenly starts to sound really mean and accusatory. I wrote to the zoo and asked them to send me a pet. They sent me. An Elephant. Only she’s too big (!). So I sent her back. A lion. She’s too fierce (!). So I sent her back. A camel. She’s too grumpy (!). So I sent her back. A snake. She’s too scary (!). So I sent her back. You know: what’s “normal” if it’s “him” isn’t if it’s “her” = purest ideology.

Another example: I went to go and see the new High Rise film in the Barbican (and this is totally obvious and should go without saying: but man: if you’re going to go and see High Rise: you should totally go and see it in the Barbican). Before the film started they showed a short film called “A Brief History of Princess X” by Gabriel Abrantes. It’s about a sculpture called Princess X by the artist Constantin Brâncuși which is supposed to be rendering of Marie Bonaparte but well – kinda looks like – hey: see for yourself. And there’s a bit in the film where someone is like: hey – that looks like a cock and balls and the narrator is all: “oh no – that’s not what the sculpture means. It’s actually Marie Bonaparte.” and well yeah: I kinda thought that was totally weird. That there could exist an object that totally looks like a cock and balls: but that if you say – hey: that looks like a cock and balls to be overridden and be told from a position of authority: oh no – you’re mistaken. That’s not what it means. It’s actually Marie Bonaparte. The meaning has been affixed there by the artist / the art world / society / etc whatever: so that the thing that looks like a cock and balls is actually Marie Bonaparte.

But hey you know: if you like thinking about this stuff – there’s lots of other examples of things like that floating around. The favourite example that springs to my mind is Chomsky describing austerity as class warfare, or the Israel Defense Forces military system being called “David’s Sling” (!!!?) but whatever. For me what’s important is calling bullshit on this kinda stuff so that we can start tearing off the bandages from our eyes and hopefully start seeing our world more clearly.

The High Rise film (Directed by Ben Wheatley! Written by Amy Jump! Starring Tom Hiddleston, Jeremy Irons, Sienna Miller, Luke Evans, and Elisabeth Moss! Based on the book of the same name by J.G. Ballard!) is another good example. I mean: fuck. Does it make sense to say I kinda enjoyed watching it but also at the same time I thought it was bullshit?

To try and keep things simple: what was the point of the film? Yes yes. It’s based on the J G Ballard and everyone knows that J G Ballard is serious and smart and respectable: so you know – let’s take things seriously (I mean LOL: back when he started he was just a crazy sci-fi writer making up various apocalypses: but hey – that’s what happens when you get old: you become respectable – whether you want to or not). But yeah – High Rise The Movie: I mean: it’s kinda easy to say what it’s about and the “themes and questions” it raises: you know – modern living, class warfare, the future being the past, erm – something about capitalism? gender roles? and errr our resources running out? and Tom Hiddleston is a very attractive man isn’t he? But erm guys: where’s the actual insight? I mean: is the film a allegory? If so: then for what? Or is it supposed to make you feel something: if so – then what? Does it have some sort of lesson to impact? If so what? I mean: hell: maybe you and your friends got something out of it and can send me a postcard or leave something in the comments: but for me – I mean – the experience of watching it was kinda fun: but it all just felt kinda meaningless. In that: there was no meaning being imparted to me by the images and sounds I saw. It was just stuff and stuff and stuff.

MAZIN: I think the problem with the film if anything is that it tried to mean something. The worst part was the coda, which reminded me of that awful artsy violent Danny Dyer of all people films, where the woman gets object raped by the impotent yob and there’s a montage of atomic explosions and Churchill photos. Lots of Ballard books have ideas but they don’t mean anything. They’re thought/social experiments. The much-loved Manhole 69 (snarf) doesn’t mean anything? Doesn’t have anything to say beyond : sleep deprivation is bad? Snip off its last bad coda, then High Rise the film is entirely about sensory stuff (and the humour, although that could have been even MORE Britishly absurdist).

I feel like maybe I’m being a little unfair picking on Mark Kermode Observer review but it’s kinda exactly what I’m talking about: I mean it’s just skirts all the way around the houses without really saying anything. The film is based on a book (which apparently is “prescient”? does this mean that it predicted The Raid and Dredd? I dunno). It’s made by film-makers who have made other films. Here is some stuff that happens in the film. Here is some stuff that happens in the film. There is apparently a “tough sheen of the sociopolitical satire” (but satirising who? and what? and how?). Here is some more stuff that happens in the film. Here are some references to other things. And then this paragraph at the end:

I mean: nice use of alliteration Mark: but (again): what the hell does that mean? I mean: you make yourself sound smart by dropping in your references: but there’s no insight. There’s no goddamn meaning.

Another example of what I’m trying to say maybe: there’s this Will Self article about the film (What would J G Ballard have made of the new High-Rise film?) which has this bit that I found kinda interesting:

“When it was announced in the early 1990s that David Cronenberg was to adapt Ballard’s apocalyptic tale of autogeddon, Crash, and moreover set it in Toronto, I was so exercised that I phoned the writer. “You can’t let him do that, Jim,” I protested (or words to that effect). “Crash is one of the great London novels. The city demands that it be set right here!” He was having none of it and gently talked me down: the point of the novel was to describe a global phenomenon, one Ballard termed “the death of affect”. It was quite irrelevant which city the film was set in – the important point was that Cronenberg’s affectless vision and planar cinematography, all lit at operating-theatre strength, strongly resonated with Ballard.”

Erm. What does this mean? Crash is one of the great London novels? Because it’s set there? Or something else? I mean: what does it mean to say that something a novel is London? I mean: I get that How The Dead Live is kinda a London novel: because a lot of it is about various bits of London under different names. Or you know: Neil Gaiman and Neverwhere. But apart from that – I mean: Ballard just seems to like how Cronenberg’s films look: which is all that’s important. But erm: if how the film looks is all that’s important – then what’s happening to the meaning? The meaning of the novel can’t be in how it looks: because a novel (non graphic obvs) is just words on a page. Maybe for Ballard the meaning isn’t that important? In which case: well – ok. Fair enough.

(Actually – I was emailing a friend and wanted to look up the opening line of the novel about the dog-eating and instead found a page of – oh my god – totally awesome quotes from the book including:

“First she would try to kill him, but failing this give him food and her body, breast-feed him back to a state of childishness and even, perhaps, feel affection for him. Then, the moment he was asleep, cut his throat. The synopsis of the ideal marriage.”

“A new social type was being created by the apartment building, a cool, unemotional personality impervious to the psychological pressures of high-rise life, with minimal needs for privacy, who thrived like an advanced species of machine in the neutral atmosphere. This was the sort of resident who was content to do nothing but sit in his over-priced apartment, watch television with the sound turned down, and wait for his neighbours to make a mistake.”

“He methodically basted the dark skin of the Alsatian, which he had stuffed with garlic and herbs. “One rule in life”, he murmured to himself. “If you can smell garlic, everything is all right”.”

And well yeah: the pleasure/jokes here comes from how the words work: and although I guess there are parts where the film attempts to recreate these stuff – it’s like trying to get across a song by painting a picture of it… But also: well the meaning here (going from the quotes at least) is just the fun of the book itself: again with a music example: it’s the pleasure of the notes second by second as opposed to there being some greater meaning contained in the whole thing: which yeah I guess is part of why Ballard is a genre unto himself).

I mean: at this point you’re maybe saying – well: what do I mean by meaning? And fair enough. But hey that Dear Zoo example from before. That’s a story where the meaning is how one way using “He and Him” the story is neutral while with “She and her” suddenly we’re getting cruel and accusatory and isn’t our society all messed up?

To which you say – well: ok. Well: maybe the meaning of stories gets more tricky the longer they go on for? To which I say yeah – ok. Fair enough.

And then maybe you say: and hey – meaning isn’t that important? Maybe you should think of stuff more like music you know? Not all music has to have meaning. I mean: if it doesn’t have any words: then really there’s no meaning there is there? To which again I say: well fair enough yeah exactly.

Which omg finally (funnily enough) brings us back to Nameless…

But that’ll have to wait until next time.

(Part 2 here).

The bit I found most objectionable about that Will Self quote was this:

I was so exercised that I phoned the writer. “You can’t let him do that, Jim,” I protested (or words to that effect).

I shall now paraphrase the above, filtering it for ego-residue so the self-regard shows up more clearly: “I knew JG Ballard. I fucking knew him. Jim, I called him, not JG or Ballard or anything like that. I had his fucking phone number, I called him loads. None of you can say that, can you? And thus my opinions have the seal of authority. God, I'm so fucking integral to English literature!”

LikeLike

All the same, I think the points he makes – when parsed and scrubbed and boiled and steamed and left to dry for a few weeks on the windowsill where they also provide an effective deterrent to slugs and snails – are fairly straightforward and kinda banal in a lit. supp. kinda way. Take the above example: Will is aghast that the Crash movie isn't set in London because he feels it captures something essential about modern London life especially in those western suburbs where it all gets creepily anonymous and emotionally blank. So he calls Jim to tell him. Jim says, nah, no worries Willy mate, the process I was describing – the concreting over of the human soul – is happening in every city on the planet, that's kind of the point I was making, using my own patch – Ealing, Heathrow etc – as the lens. Job done.

But to listen to old Willy boy carry on, you'd think his utterances were the infitiely careful discriminations of massive floating TS Eliot head, bigger than a cathedral, shooting coffee spoons from its nostrils.

The moral – don't consume to much Self as he will rot your brain teeth to gloomy stumps – you're welcome!

LikeLike

(1) “There is apparently a “tough sheen of the sociopolitical satire” (but satirising who? and what? and how?). Here is some more stuff that happens in the film. Here are some references to other things.”

It feels like maybe what you're saying here is “I don't like reviews, I prefer close reading.” Which is cool – I don't, and I do – though there's perhaps a point to be made that what someone like Kermode is doing isn't so much exploring the themes or styles of a work so much as providing consumer advice.

I'm happy to take the cunt out of it on that basis – and this style of review definitely flatters a sort of obviously “deep” product – but I think that by suggesting meaning / style / import in a straight and snappy style, that review is pretty much fulfilling its function.

Shitty function.

Shunction.

LikeLike

(2) “Ballard just seems to like how Cronenberg's films look: which is all that’s important. But erm: if how the film looks is all that's important – then what's happening to the meaning? The meaning of the novel can't be in how it looks: because a novel (non graphic obvs) is just words on a page. Maybe for Ballard the meaning isn't that important? In which case: well – ok. Fair enough.”

In a sly improvement on your original draft, and a pre-emption of my next point, you follow this with examples of the style of Ballard's novel – its most substantive element, or at least the one most worthy of the attention of reviewers and potential move makers alike.

Still, it's an accident that's only narrowly avoided, because this paragraph comes dangerously close to reducing prose/poetry (the latter being your favourite, I know, but bear with me – “words on a page”) to pure information. There's meaning in Ballard's work – as I suggested in my reaction to the movie, High Rise as a novel collapses the social into the biological, the architectural into the internal, and in doing so suggests that our grand schemes may have more in common with our base reactions and desires than we might like to think – but this would be trite and commonplace were it not for how it's conveyed.

LikeLike

(3) “But also: well the meaning here (going from the quotes at least) is just the fun of the book itself: again with a music example: it's the pleasure of the notes second by second…”

Speaking of which! And yet there's a danger here too, of splitting art into two camps – the Meaningful and the Musical – which obscures the fact that while “it's all subjective, maaaan” we can try to meaningfully convey the experience of a work of art, taking into account its overall structure and impact, without necessarily distilling all of this to A Lesson, like something out of a children's book.

Yer man Mazin is 100% correct when he says that the bits of High Rise (the movie) that do this are The Worst.

Jumping ahead to the next, as-of-yet unpublished section of this post in which you discuss Nameless, and claim that its scenes could be rearranged in any order without damaging the meaning: bullshit.

The series is built on a series of carefully positioned breaks, disturbances – moments where the whole mode of the series seems to slip. So: we settle in to the shifting dreamscapes, the way the story drifts from the Botanical Gardens to the underworld, only to find ourselves in space. We settle into Armageddon by way of Mountains of Madness (haha, such a shite description – these duff pitches are fun to do though so I can't blame baldo for putting one in even though it's a totally rubbish moment) only to wake up as stump-meat/as a survivor of great trauma, with secret origin and terrible mission jostling for primacy. There is no settled meaning, only an endlessly adaptable ache for one.

Morrison's best work provide a more profound and diverse experience, and there's always scope to rehash the Lukacs/Bloch argument about subjective expressionism vs. art that tries to provide an account of some sort of totality, but Nameless is still an affecting ride through the forest of dicktrees, to the extent that – aow – it's sometimes hard to keep your eyes open while you – ooft – read it.

Of course, “meaning is slippery, wooo!” isn't a message that's going to hit anyone like a bolt of lightning in 2016. Thankfully Nameless isn't a postcard, or a text from a knowledgeable uncle – it's a simulation, a fake experience. It's dinner.

Burnham's art is the meat, all tough with gristle and so raw inside that you have to avert your eyes before you take a bite; the colour's the hotsauce; the structure, the bread, soiled with unspeakable juices so the whole thing slips through your fingers.

LikeLike

(4) Now I'd apologise for responding to something that's not happened yet, but… well, if it turns out you've edited your essay to the extent that none of the above applies, the desired effect will have been achieved.

If, meanwhile, the section is there intact, the effect remains, with the above message acting as an unpleasant break in the chronology. A pricking in the eye from a flapping branch on the great dicktree of the internet.

Either way, there will be something off about these posts and the responses to them; an interrupted chronology that tells its own story; a disturbed experience. They will not read as they would have if I had not chopped and changed them, unless you delete all these comments and restore the original order, or – more likely, but allow me this bullshit hubris – people just don't read the comments.

I done a thing. Congratulate me.

LikeLike

Re: “You can’t let him do that, Jim”

Images of Will Self as Dr McCoy swimming in my head. Can we make this into reality please please?

LikeLike

Re: Kermode as consumer advice.

No. Fuck that. I mean – sure yeah ok maybe that's the stated intention and maybe that's what it started with. But (very sadly) humans work out how to think about stuff by paying attention to how other humans think about stuff. And Kermode (love him or loath him) stands astride the culture like the Colossus of Rhodes and (as strange as it sounds) thousands of people (at the very least) look up to him as an example of how to think about films and – what do they get? – fucking superficial light-weight musings that don't mean anything at all apart from “oooh – this will make me sound clever” which (in my eyes) is basically the main problem of western society.

Yes – I'm tracing a line from his shitty little film reviews to the countless evils of Capitalism which is probably makes me sound like a crazy person I know. But – damnit – how we think about things is IMPORTANT. And if you're reading this and don't think that's true then um – maybe you're thinking about it enough?

LikeLike

Wouldn't disagree that how we think about things is important, and re: consumer reviews I *did* say I was happy to take the cunt out of Kermode's work on the grounds that it fulfils a shitty function/shunction.

I just think this means that Kermode's work isn't the best evidence of the quality or otherwise of Ben Wheatley's High Rise. He'd write the same sort of thing about something that satisfied you as he would about something that didn't, right? That's just how he does.

LikeLike

I'm not sure that I either love or loathe Kermode, personally. Some of the stuff he's written on the role of the critic/the economics of blockbusters, what “failure” looks like for big movies etc was maybe quite informative, I think? It's been a while so I can't honestly say for sure, which probably suggests that it wasn't as memorable as it could have been.

Well either that or that I'm just a fucking idiot :-p

Anyway, as I said, Kermode fulfils the role of a consumer reviewer quite well, but I'm not mad keen on that role. “Consumer advice” presupposes consumers, for one thing, and perhaps also that art may be contained in that framework.

There's maybe an interesting question of how you view trust here though, plus how much influence you ascribe to the reviewer. Like, if someone listens to Kermode's (in your opinion and probably in mine too) shallow babble then goes to see a movie and finds that it causes them to feel what they expected to feel based on that representation of it, they'll probably find themselves trusting Kermode's reviews more in the future.

The sticky question is whether or not this limits the viewer's reactions to those outlined by Kermode or not – if so, that's bad right? The audience is learning to react in fairly narrow and limited terms.

I'd be a bit more skeptical about this though, for the very reason that I don't think Kermode's writing is powerful enough to dominate the brain like that – it could maybe work as a “tip of the iceberg” thing, maybe? I'm an egotistical prick with Big Opinions, so I could be underestimating how deep into the souls of his readers Kermode can reach.

Still, “Mark Kermode can successfully identify the tip” – he should put that on the cover of his next book.

Anyway, this is still far from my ideal version of what Writing About Stuff looks like, but I dunno – thoughts?

LikeLike

Being skeptical = expressing scepticism over a hot grime beat, obvs.

LikeLike