Jack Kirby (born Jacob Kurtzberg) didn’t want to be called ‘King’ but the veterans in the offices of Marvel comics insisted. Kirby has become one of the most celebrated of comic book artists from the era of the superhero boom in the 1960s. In fact, he produced a variety of work from 1941 to 1993. But did he have a vision or point of view? Was he only a good Illustrator of other’s ideas, not an artist with his own, like a Caravaggio or Rembrandt? I had the idea of doing a slide lecture on this very subject, because 1) I think nothing works in the medium of slide projection like comic book panels, and 2) this would emphasise that Kirby’s themes are realised through his art work.

It was said, back in the 1970s, that Kirby “couldn’t write”, and then the award is passed to Stan Lee his editor and colleague at Marvel. But what Lee was famous for was the short-cut technique of the ‘Marvel method’: he’d supply a two page synopsis of a story and let the artist rip. Sometimes he would act out characters and story ideas to give a basic outline or, as once, just told Kirby to let the Fantastic Four fight God i.e. Galactus. Lee would then write dialogue balloons and even request changes but he wouldn’t supply the conventional panel by panel ‘screenplay’. So, there was plenty of room for artist invention. Certainly, it was Stan Lee who, with the Fantastic Four, came up with the Marvel formula of superheroes having human problems, but it was Kirby in his art that combined suffering humanity with grandeur, especially in his great decade of 1963 to 1973.

Let’s see what aspects, 1-5, made Kirby a distinctive artist?

1) STOCKY RATHER THAN STOCK

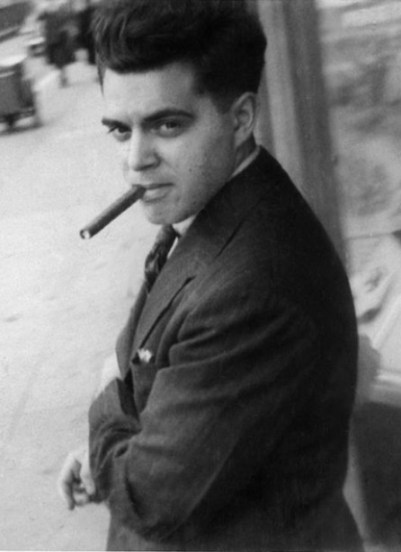

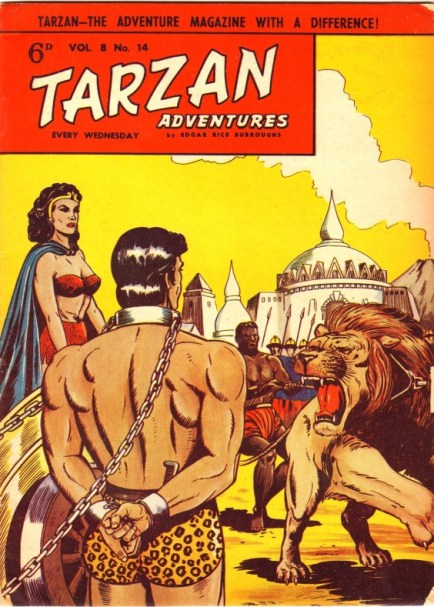

Kirby was a working class Jewish boy in New York, growing up on the streets of the Lower East Side in the 1930s. No doubt he heard the old folk tales of his Austrian migrant relatives, like the Norse sagas, or even the Jewish legend of the Golem, but he also admired the strips of his artist-hero Hal Foster of Tarzan (1929-37) and the knights and castles of Prince Valiant. He paid regular visits to the movies.

When he was older, Kirby joined the Boys Brotherhood Republic, a self-help boys club set up in 1914 with its own boys government including mayor and treasurer. He already believed in standing by the group – he was part of a street gang, not all of whom were perfect specimens of ‘jock’ fitness. Kirby himself was always short and stocky as he was as a boy. When he and Joe Simon invented their first superhero, just before America entered the war in late 1941, they choose a seven-stone skinny boy called Steve Rogers who had the luck to be born in a time and place when science could turn him into that super-athlete Captain America. Kirby too served as soldier in Europe during that war.

One of the recurring figures in Kirby’s art is the boyish hero – a short squat type, not a fully grown man like Superman or Green Lantern, but a figure seeming just shy of maturity who appears smaller than others: such characters as Kamandi, the Silver Surfer, Orion, T’Challa the Black Panther and Thor. In recent movies, Thor the Thunder God is a bearded Viking; he may not be a bully but you’d bet on him in a bar fight, even without his hammer. Kirby’s Thor however often looks like a crouching youth with long blond hair and a propensity to find himself up against giants, magic forces and the arrogant Hercules. All the better to entice us juveniles that provided the take-off for Marvel’s success in the ’60s. Even the Thing, Ben Grimm, that marching rock-pile with the deadly finger knockout, could sometimes appear as petulant and put-upon as a toddler. These figures, like Jack the Giant Killer, often find themselves pitted against much larger persons, like playground bullies, often mechanical, or armoured like the Destroyer or Dr Doom. By contrast, Spiderman comes up against people as slim as Peter Parker though usually much older; Doc Octopus is a middle-aged spider. While Daredevil has the Gladiator, Bullseye and Electra, more like a wrestling match of near-equals, while the slow Kingpin is rich enough for body guards. But Kirby heroes often have to tussle with big brutes, a sight very appealing to that youthful reader who’s no quarterback.

2) GODS AND SUPERMEN

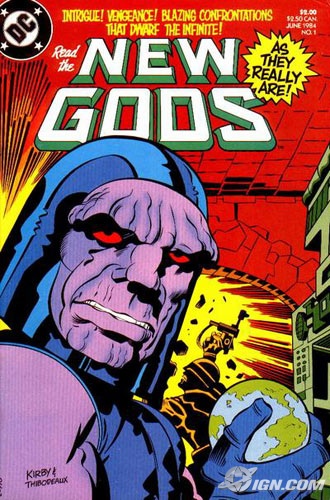

In another contrast to the boyish figure of his superheroes, Kirby soon started coming up with megalomaniac opponents. Evil Brains are of course endemic in superhero comics – Lex Luther, the Joker – but Kirby turned it up a notch, with Galactus, Darksied and indeed, Thor’s father Odin. The Thor story that started in Journey into Mystery #103, with Odin’s displeasure at his son’s disobedience, turned into a saga where elements of soap opera, clanging fight scenes and travel to many worlds resulted in a narrative that burst the confines of the single issue American comic (1964 on). The old gods gave way to new gods and it seemed Kirby couldn’t get enough of stately demagogues who reminded readers of Hitler if not the Judeo-Christian Bible. But if they were modelled after figures much grander then the megalomaniacs of other books, they could also be as fragile and just-coping as the new human heroes. Dr Doom was a case in point. Haunted by his scarred face under the iron mask, he even got his own comic at one point and tipped over into pathos entirely.

When Kirby went to DC in late 1970 and created the saga of the Fourth World, running across several separate books, he created the antagonist Darksied. Though he looked like somebody else’s chief thug, Darksied had none of the hysteria of previous super villains. He was born into a ruling aristocracy and was just calmly fulfilling his inheritance by searching for the control over all life. Not a screaming Hitler or another inmate of Arkham Asylum but the son of an achieving family, ready to acquire even more resources, like the Anti-Life Equation, with which to reign. Very human.

Most of Kirby’s villains were just that bit more magnificent, but not even they were allowed to be “supermen” – or super demons – distant from our desires and anxieties. It was as if Kirby wanted to deny even Hitler a personified grandeur, even as the great Satan. His villains may have aspired to be gods but even they were flawed.

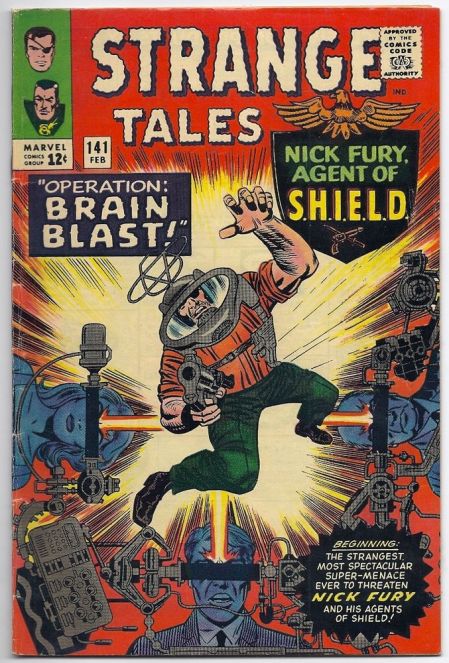

3) ‘KIRBY TECH’

Kirby’s art is famous for its depiction of machinery: Kirby-Tech, thick, complex, gadgets crackling with dark spotted energy. But, though fascinated, Kirby shows that not even advanced technology is a vehicle bound straight for glory.

One of Kirby’s most interesting gadget interfaces in the Sixties was Nick Fury, newly co-opted director of SHIELD, up against the semi-fascist hood wearers of the Hydra organisation. Fury is a veteran of the Second World War and no PhD, but he’s not above using flying cars, deep diggers and brain helmets. Nevertheless, he is an action hero who prefers putting his body and cunning up against the foe. He’s not like the crew of the Starship Enterprise, semi-dependent on their ship and their weapons, phasers and communication devices. Fury, like the James Bond of the early movies and indeed the recent ones with Daniel Craig, is ready to outleap, outrun and outfight metal opponents and scientist villains. Tech is great but it isn’t allowed to tyrannise and eclipse the hero.

In the Galactus trilogy (FF #48-50), the master conqueror’s lieutenant, the Silver Surfer, is won over not by ray guns or judo throws but by the arguments of Alicia Masters, Ben Grimm’s lover. She challenges the Surfer as to why life on Earth should be extinguished. The Surfer is swayed by her appeals and rebels against his master. How many people in mid-1966 made the analogy with the questioning of the US war in Vietnam that was only then starting to escalate? Kirby was not being trendy in his protest but just following the human story as well as collaborating with his editor Stan Lee. Lee had recognised that if the Surfer could be a long-running commercial property, the story mustn’t turn him into a louse.

4) IN THE FAMILY

Initially, Stan Lee’s Fantastic Four, even without costume uniforms, had problems with their psyches and each other. They were extraordinary in abilities yet by no means superb in how they handled other people. Yet Kirby went further. As the FF line continued, he began to introduce new worlds, hidden lands, territories beyond the hideout of any criminals. His art also excelled at close-up emotion, not only physical combat but expressions of pain and anxiety, pleasure and elation, even in the body language of Dr Doom’s armour.

In his New Gods comics for DC (1971-2), Kirby took over the scripting function entirely and produced a saga of various worlds with a variety of imperfect characters.

All his invented landscapes (including Asgard and Olympus) suggest he was continuing the tradition of the Lost World, that late-nineteenth century imagining of places often underground or among mountains – She; The Land that Time Forgot; etc. Kirby’s first of his own created ‘worlds’ was the Refuge of the Inhumans (FF#45) whose royal family started out as opponents of the FF but turned into something much more ambiguous. Though the Inhumans were afraid of anyone encroaching on their hidden land, the greatest actual threat came from within, from Maximus the brother of their leader Black Bolt. Here Kirby makes no good-bad, foreign-national oppositions; the enemy is a part of the family and nation.

Black Bolt is majestic in his silence but as he doesn’t speak, he listens and must have his thoughts communicated by Medusa his colleague and spouse. Maybe this makes him a better ruler, mulling over the problems of his realm, like his brother.

Speaking of Medusa: if Kirby had been younger, maybe he might have gone further in his depiction of women. He might have become familiar with milieus like those displayed in the 1970s TV series Charlie’s Angels – entertainment, fashion, prostitution. Who knows what we might have received from his invention? His female characters might have come up with projects of their own and done their work without male command, as Simone de Beauvoir wanted. As it is, writers and artists still reproduce the situations he did come up with, where women fight alongside men or speed them into battle from gleaming bases.

5) A JEWISH ARTIST?

Kirby’s art, and consequent stories, have been called Shakespearian plus advanced technology, though the Homer epics with their warriors and wanderers might be closer to the mark. Another reference point is to call them Jewish. In fact the whole Marvel idea of “superheroes with problems” could be seen as an alternative to a hegemonic Christian notion of the holy warrior as exemplified by knightly heroes like the Lone Ranger, Prince Valiant and the DC roster. Kirby grew up in a certain neighbourhood at a certain time where there was a strong emphasis on family, area protection, a sense of international persecution (Hitler) and solidarity (the Boys Brotherhood Republic). Kirby was neither a religious nor a nationalist Jew (a Zionist). Rather, in US terms, he was a liberal and a Democrat and, in global terms, a progressive proletarian, like Philip Roth, Leon Trotsky and Franz Kafka. He grew up an East Side New Yorker in the1930s when Jews felt endangered by fascism aboard and at home. Always generous, he sided with other ethnicities (the Black Panther) and rooted for the ‘left’ President Roosevelt. Kirby believed that life meant a hard fight but also a struggle for human good in this world.

CONCLUSION

Kirby’s art and storytelling displays characteristics often downplayed in other Marvel and DC product. Portraying flawed often ugly and boyish heroes, ambivalent towards gods and ‘supermen’, with an emphasis on antagonistic parent-child analogies, a belief in science but also human morality as a struggle in this world for the common good. He proved to be more than an illustrator of someone else’s script, for he often lacked a full script or wrote his own over sequential panels, as at DC. Even when, like a sixteenth century artist, he started with someone else’s idea – as they were given a Bible story and a church to decorate – he would put his own spin on it with his style. He was the inventor of a distinctive imagery, the shaper of a distinct vision.

At Marvel or DC, Kirby’s storytelling panels appealed to the imagination of a lot of readers, mainly young males, and in so doing created templates for later comics. Stan Lee is once supposed to have told Marvel artists, “Draw like Kirby!”, the ultimate compliment. It was Kirby’s imperfect superheroes that also provided a basis for later new departures in the hero ethos, such as the recent one of the corrupt superhero who might domineer over others (Powers, the Authority). The dynamic action style of Kirby’s line delivered a vision of a hard world where, though not super-perfect, these beings still fought for the right and the human against the mighty – stocky Davids against tyrant Goliaths.